Over the last year, I—Jeen—found myself returning to the same uneasy question:

If organizations are reducing people while investing heavily in AI, what actually happens to technical documentation?

This question didn’t come from curiosity alone. It emerged from watching software teams move faster, documentation roles shrink or disappear, and AI tools quietly enter workflows without clear ownership or process.

Process and procedure documentation, in particular, has always depended on human effort. This includes attending product demos, testing applications, deciding what should be documented, structuring content, reviewing accuracy, and maintaining lifecycle governance.

What’s often missing from this conversation is realism. AI can generate text, but documentation is more than writing. It is a system of understanding, structuring, validating, reviewing, publishing, and maintaining knowledge over time.

This article is not a case study, and it does not claim that companies have already solved this problem. Instead, it is an attempt to think through—step by step—how documentation could function in an AI-led environment without losing accountability, accuracy, or trust.

The focus is not on whether AI will replace humans, but on how the Documentation Development Life Cycle (DDLC) itself may need to change when people are fewer, systems are more complex, and expectations continue to rise.

AI is increasingly present in documentation workflows, but it has not replaced the need for human judgment. Technical writers remain essential—not as content factories, but as reviewers, architects, and governors of documentation systems.

When leadership views AI as a force multiplier rather than a headcount reducer, documentation becomes more reliable, scalable, and accountable. This balance—AI execution with human oversight—is the foundation for sustainable documentation in modern software organizations.

Rethinking the Documentation Development Life Cycle in an AI-Constrained World

When Technical Documentation Depends on People Who No Longer Exist

Software organizations are moving faster than ever—shorter release cycles, continuous deployment, and rapid feature iteration. At the same time, many of these same organizations are reducing headcount, including dedicated technical writing roles.

The problem is not that documentation is suddenly less important. In fact, the opposite is true. As systems become more complex and regulated, the need for clear process and procedure documentation increases. What has changed is the assumption that there will always be people available to do the work.

Traditional documentation models rely heavily on human involvement at every stage of the Documentation Development Life Cycle (DDLC):

Attending product demos, manually testing workflows, deciding what should be documented, structuring a table of contents, writing step-by-step procedures, coordinating reviews, publishing updates, and managing archival and compliance.

When those people are no longer available—or are spread too thin—documentation begins to fail in predictable ways.

Documentation Falls Behind the Product

Features change faster than documents are updated. Procedures no longer match the UI. Users lose trust and turn to support or tribal knowledge instead.

No One Owns Structure or Consistency

Without a dedicated role, decisions about what to document and how to organize it become ad hoc. Content grows organically, inconsistently, and without a coherent information architecture.

Review and Governance Are Quietly Skipped

Under delivery pressure, review cycles shrink or disappear entirely. Accuracy checks become reactive rather than systematic, increasing operational and compliance risk.

In response, many teams experiment with AI tools—asking them to “write documentation.” But without redefining the DDLC itself, this approach only automates fragments of a broken system.

The real problem is not whether AI can write. It is that documentation processes were designed for a people-heavy world that no longer exists.

An AI-Led, Human-Governed Documentation Development Life Cycle

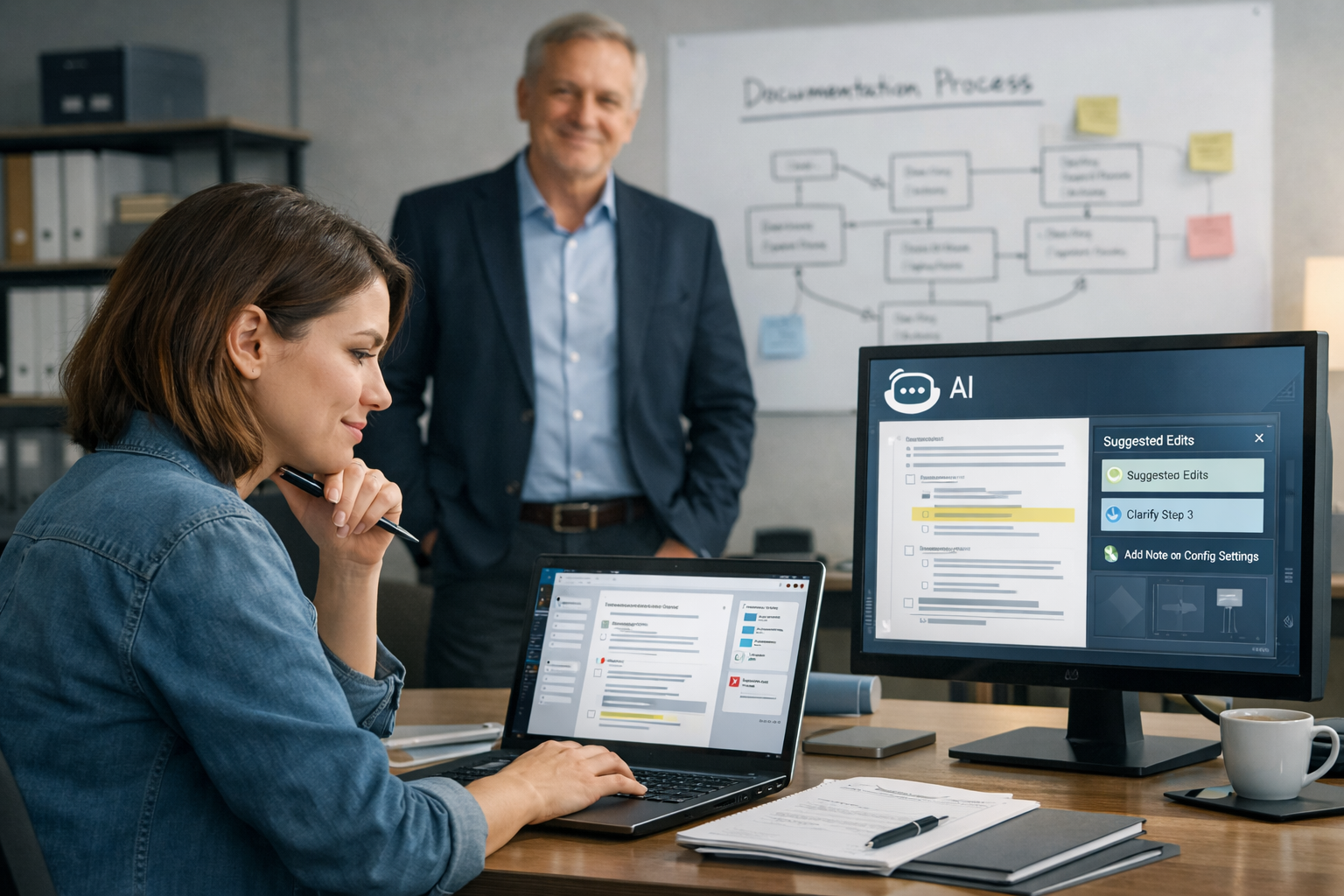

The solution is not to replace humans wholesale, nor to treat AI as a shortcut for writing. The solution is to redesign the Documentation Development Life Cycle so that AI executes repeatable tasks, while humans retain governance, judgment, and accountability.

In this model, documentation becomes a system—one that can operate reliably even when teams are smaller.

Step 1: Information Gathering and Product Understanding

Instead of relying on a writer to attend live demos and manually test features, product understanding is captured through structured inputs: recorded demos, automated UI tests, logs, PRDs, user stories, and API specifications.

AI analyzes these inputs to extract workflows, actions, inputs, and outcomes. Humans validate understanding at a high level rather than recreating it manually.

Step 2: Audience Analysis and Table of Contents Creation

AI generates candidate tables of contents based on user roles, feature sets, and usage patterns. Multiple structural views—task-based, role-based, or feature-based—can be produced quickly.

Humans approve the structure, ensuring it reflects real user needs rather than theoretical completeness.

Step 3: Content Development Using Standard Templates

Documentation templates define the required structure: purpose, audience, prerequisites, procedures, inputs, outputs, and error handling. AI populates these templates consistently using extracted product data.

This shifts human effort from writing every step to defining standards that scale.

Step 4: Review and Quality Assurance

AI performs first-pass reviews for clarity, consistency, and template compliance. Automated checks validate procedures against test cases and system behavior.

Human review focuses on high-risk, customer-facing, or regulated content—where judgment matters most.

Step 5: Publishing, Maintenance, and Archival

Documentation lives in version-controlled systems aligned with the product lifecycle. AI detects changes in code, UI, or configuration and flags documentation for updates, deprecation, or archival.

Humans define governance rules; AI enforces them consistently.

The result is not “AI-written documentation,” but a documentation lifecycle that can function with fewer people and fewer bottlenecks.

Signals That This Model Is Already Emerging

This approach is not presented as a finished industry standard, and there are no polished case studies to point to yet. That absence is important—and honest.

Instead, the proof lies in observable signals already shaping how documentation work is being done.

AI Is Already Producing Draft Documentation

Teams are already using AI to generate procedural drafts, summaries, and rewrites. What is missing is not capability, but structure and governance around how that content enters the DDLC.

Documentation Inputs Are Increasingly Machine-Generated

Automated tests, system logs, recorded demos, and API specifications already describe how software behaves. These inputs once had to be interpreted manually; now they can be analyzed directly.

Review Cycles Are Already Being Compressed

In many organizations, full editorial and SME reviews no longer happen consistently due to time and cost constraints. Risk-based review is not a future idea—it is already an informal reality.

Docs-as-Code Practices Are Widely Accepted

Version control, CI/CD pipelines, and change tracking are standard in engineering. Extending these practices to documentation maintenance and archival is a logical continuation, not a leap.

The strongest signal is organizational pressure itself. When expectations increase and resources decrease, manual, human-only documentation models stop scaling. The AI-led DDLC emerges not because it is fashionable, but because alternatives quietly fail.

Documentation That Scales Without Losing Accountability

The promise of this model is not perfection, and it is not the removal of humans from documentation. The promise is sustainability.

By redesigning the Documentation Development Life Cycle (DDLC) around AI execution and human governance, organizations gain documentation that keeps pace with the product—even as teams become smaller.

For Engineering Leadership

You gain predictable documentation coverage, reduced operational risk, and a system that aligns documentation maintenance with software delivery—without requiring proportional headcount growth.

For Documentation Professionals

You move from being the sole producers of content to the architects of documentation systems—defining standards, reviewing high-impact content, and safeguarding quality where it matters most.

For the Organization

Documentation stops being a fragile afterthought and becomes a durable, governed asset—one that supports users, reduces support load, and stands up to audits and change.

AI does not replace accountability. It makes accountability possible at scale.

The question that started this exploration—what happens to documentation when people are fewer and AI is more present—does not have a single final answer.

What is clear is that documentation can no longer depend on individual effort alone. It must be designed to operate under constraint. An AI-led, human-governed DDLC offers one way to do that—by making documentation deliberate, durable, and accountable.

The future of technical documentation is unlikely to be fully human or fully automated. It will sit somewhere in between, shaped by systems, guided by judgment, and built to endure change.

Continuing the Conversation

This article reflects an ongoing exploration of how technical documentation evolves in an AI-constrained world. If you’re navigating similar challenges, I’d be interested in hearing how your teams are approaching them.

You can continue the conversation by visiting the contact page and selecting “Documentation Strategy Conversation” from the service list.

If it helps, you can share:

- How documentation is currently created and maintained in your team

- Where AI is already being used—or intentionally avoided

- What has become harder as teams scale, shrink, or reorganize

There’s no fixed format. I read and respond personally, and where patterns emerge, they often inform future articles and research.